At Brantley Andrews’ two-month checkup following major surgery, the 5-year-old was running down the clinic hallway without braces. At home, he was jumping on the trampoline and playing outside. This is a stark contrast to what his parents heard when he was 4 months old: that he’d never walk and would probably live his life in a wheelchair.

As a preemie born at 32 weeks, Brantley experienced a world with challenges and delayed milestones. Physicians and experts couldn’t explain why he cried all the time and didn’t move – even at 10 months old. Looking back, they now realize his limbs were tight with spasticity, and he was in pain. An MRI taken at the time showed brain damage, yet the neurologist reported it normal. He also had cerebral palsy, but that diagnosis wasn’t revealed until he was 18 months old.

“Once we got the cerebral palsy diagnosis, it was kind of a relief. We felt like we could breathe for the first time because we knew what was going on,” said Brantley’s mom, Brittany Andrews. “Before, it was just a guessing game.”

Brantley started walking at age 2 ½, yet still experienced pain, was clumsy, and didn’t sleep more than three hours a night – with lots of napping. His body tired easily and required days of rest if he played too hard. Brantley received Botox injections to provide relief for the spasticity, but it was only a temporary fix.

Selective dorsal rhizotomy procedure

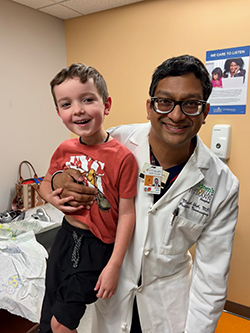

A cerebral palsy Facebook group led the Andrews family to Manish N. Shah, MD, a pediatric neurosurgeon with UT Physicians Pediatric Surgery – Texas Medical Center. The family was exploring different treatment options for Brantley, since he lost mobility whenever the Botox injections wore off.

The family learned Brantley was an excellent candidate for a selective dorsal rhizotomy procedure, based on findings from his MRI and physical exam. His MRI showed scarring that is typically caused by bleeding in the brain at premature birth when the blood vessels are more fragile. This scarring, periventricular leukomalacia (PVL), reveals the cause of spasticity in his arms and legs.

Shah recommended a 1-level laminectomy for SDR L1-S1, which he performed in January 2024. Selective dorsal rhizotomy (SDR) is a well-established surgical procedure for improving lower-extremity spasticity in children with cerebral palsy. During this surgery, he opened Brantley’s back through a small incision in the spine, where the spinal cord ends, to see the nerve rootlets.

“Once we separate the motor nerves from the sensory nerves that carry spasticity, we test bundles of nerve rootlets at all the levels and cut 75% of the most spastic,” said Shah, associate professor of pediatric neurosurgery, William J. Devane Distinguished Professor at McGovern Medical School at UTHealth Houston, and director of the Texas Comprehensive Spasticity Center. “Evidence shows that if you don’t cut enough of these nerve rootlets, spasticity may return, and there is no way to redo the SDR operation.”

Brantley’s case was unique in that he was most spastic in his lower legs, said Shah. He also had significant spastic L2-L4 roots seen during surgery that were surprising based on his clinical exam.

Gaining strength through therapy

Brittany acknowledged that Brantley’s recovery from surgery was hard, especially for the first three to four days. Everything that Brantley had spent his whole life working toward (mobility, walking, and running) were lost for a few days following surgery. Although a common outcome, it was challenging for the family.

“These kids don’t have the spasticity anymore, but they also don’t have the muscle because they were relying on the spasticity to support them,” Brittany said. “It was really hard on Brantley, because he didn’t understand why he couldn’t walk and had to use his wheelchair.”

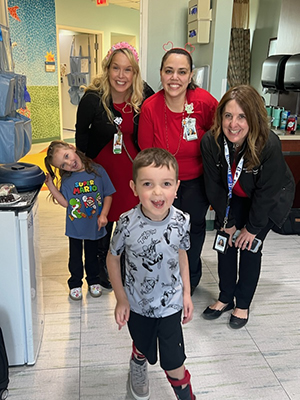

Brantley completed two weeks of inpatient physical therapy following his surgery. His mom and dad alternated staying with him every night as the other parent cared for his younger sister at home. They also worked with him in between the structured inpatient therapy sessions, which lasted three to four hours a day. The hard work paid off.

“Brantley today is happier, more energetic, and more confident,” Brittany said. “He’s more willing to try things because he’s realized he can do it. He doesn’t have the pain holding him back.”

Turning around quickly

Brantley progressed quickly through rehab because he was well-prepared for his recovery, according to Shah. In preparation for his SDR procedure, he spent countless hours in therapy to build his strength.

Patients like Brantley remind us why we do what we do — and what a life-changing impact the correct treatment at the correct time can make on an entire family.

– Manish N. Shah, MD, pediatric neurosurgeon

Shah and the team at the Texas Comprehensive Spasticity Center follow hundreds of children and offer a personalized treatment plan to each that’s based on their specific needs. The preferred timeframe for performing SDR is when kids are between 4 and 5 years old because they are most cooperative with the therapies.

“Timing is very important, which is why we follow children from a very young age – some from the NICU – to offer them the correct treatment at the correct time,” Shah said. “It’s the close working relationship among all our team members that our patients and their families benefit from most.”

Shah said it’s a privilege to be part of such a wonderful multidisciplinary team comprising the world’s experts in movement disorders: Christine Hill, PT; Stacey Hall, DO; and Simra Javaid, DO (physical medicine and rehabilitation), as well as Surya Mundluru, MD, (orthopedics) and Nick Russo, MD, and Sarah Lund-Wilson, MD (neurology).

Making the right choice

Brittany and her husband have no regrets about their surgery choice for Brantley. They also were not expecting SDR to be a miracle cure.

“We just wanted to give him a better quality of life, and the surgery has already done that,” she said. “We are so happy that we did this because it’s made such a big change.”

The team believed Brantley would walk with braces, and perhaps use a device for long distances. Yet Brantley has exceeded all expectations, Shah said.

“At two months post-op, Brantley is doing what we would normally expect at 6+ months after surgery,” Shah said. “I am very encouraged and can’t wait to see what new milestones he reaches.”

Navigating conflicting opinions

Parents are often presented with different approaches to treating and caring for their children’s conditions. Another physician had recommended a partial SDR to them because he considered SDR to be a big procedure for Brantley. Shah said this is one of the most difficult aspects for parents of special needs children.

“They are the primary decision maker for the child, and unfortunately, there are many different treatments – some not based in evidence – and biases in health care,” Shah said. “We know how important it is to make the correct choice and that all parents want to make the best decision for their children.”

Shah recommends finding a team of providers willing to work together, talk, and treat children with an individualized approach. Care for cerebral palsy is not one-size-fits-all, he said.

- Ask for evidence to support the given recommendation.

- Evaluate the experience level of the team.

- Where did the neurosurgery team learn their technique?

- How many do they do a year?

- What evidence do they use to support their recommendations and their techniques?

“Unfortunately, SDR is a surgery that cannot be repeated,” Shah said. “We encourage any family to come for a second opinion before pursuing other options.”

Turning dreams into reality

Shah said the team loves when a patient tries a new skill they’ve recommended. In March 2024, at his two-month follow-up, they suggested Brantley try using a two-wheel bicycle. The next day, Brittany sent the team a video of Brantley riding a two-wheeled bike in physical therapy.

Brittany was in tears as she watched Brantley ride the bicycle. She and her husband had been told by other doctors that Brantley probably wouldn’t ride a bike unless it was an adaptable bicycle.

“This is huge because he asked for a bike for Christmas last year. He’s wanted to do this and without SDR, he wouldn’t have been able to,” Brittany said. “It makes a huge difference when these kids are able to do things they want to do and weren’t able to before. Every milestone that he has hit has been huge!”

What’s next for Brantley? He wants to do mutton bustin’ at the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo, a rite of passage for young Texans who sit on an energetic sheep as it runs unpredictably around the arena.

His adventurous spirit already makes him a winner.