Median arcuate ligament syndrome (MALS)

What is MALS?

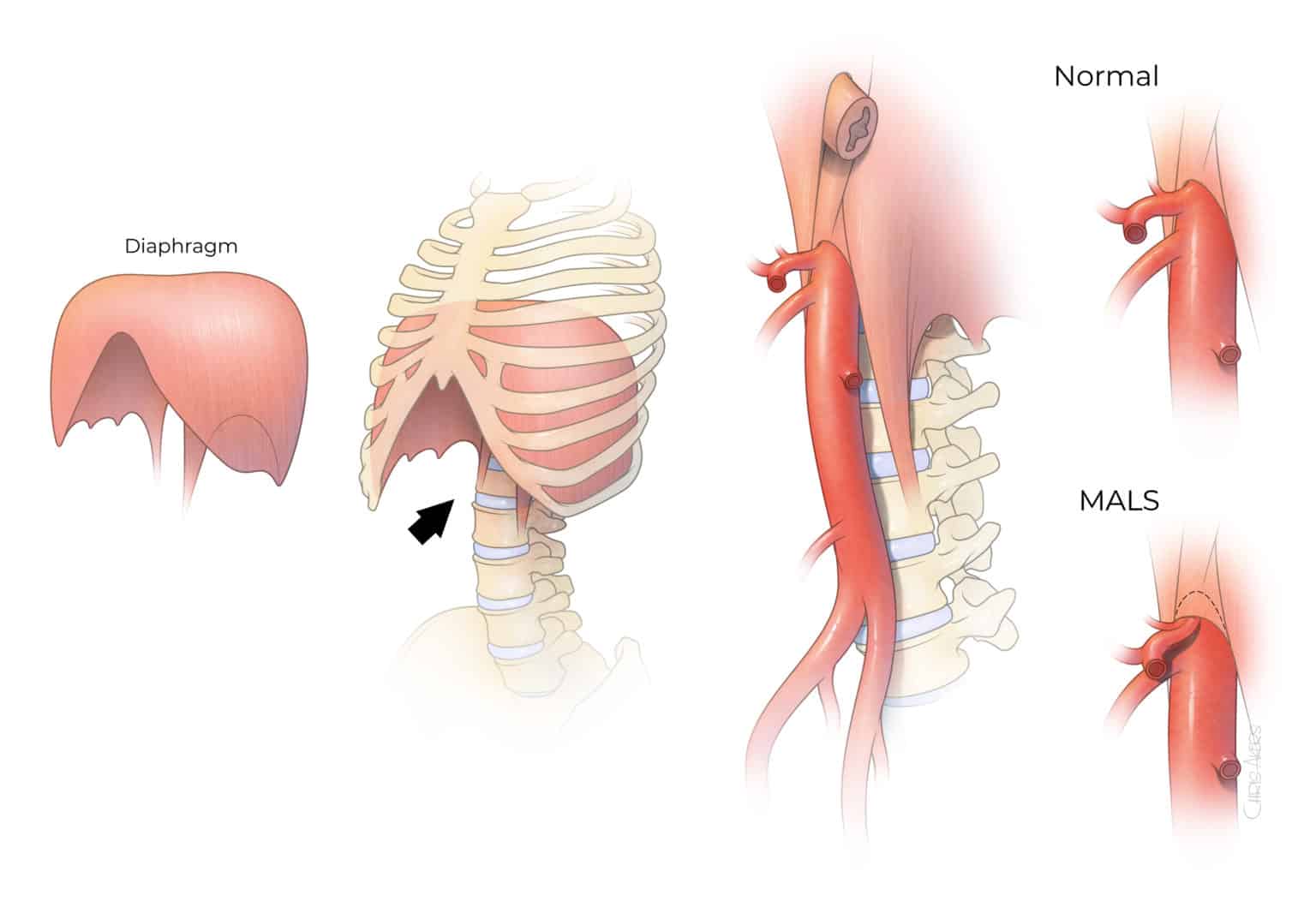

Median arcuate ligament syndrome (MALS) is an uncommon condition that predominantly affects young individuals due to excessive compression of the celiac artery, the first large branch of the abdominal aorta located near the median arcuate ligament and celiac ganglion (Figure 1). The cause remains unknown, but may be due to compression of the sensitive outer arterial wall layer by the muscle and ganglionic tissue, direct irritation or inflammation of sympathetic nerves, and possibly intermittent decrease in blood supply to the upper gastrointestinal tract. The diagnosis of MALS can be difficult because most patients present with nonspecific upper abdominal pain and because compression of the artery itself is not sufficient to determine cause and effect.

Symptoms

Clinical presentation

Clinical presentation of patients with MALS can vary from severe pain in the upper abdomen associated with meals and exercise, to more subtle abdominal discomfort, nausea, and vomiting. Because these gastrointestinal symptoms are not specific to MALS and can also occur with a variety of other gastrointestinal or abdominal disorders, the diagnosis can be challenging. Patients often require an extensive investigation with multiple consultations and diagnostic tests. In addition, because evidence of compression or narrowing of the celiac artery by the median arcuate ligament is not sufficient to establish the diagnosis and is found in up to 40% of the general population, the finding of narrowing itself does not determine the diagnosis. MALS is often considered a “diagnosis of exclusion”, which is determined after other gastrointestinal disorders have been ruled out, and is strongly supported by the presence of severe epigastric pain with concomitant compression or narrowing of the celiac artery.

Pain:

- Pain between the ribs and below the sternum

- Pain in either the side or back

- Pain after eating and/or after exercise

Additional nonspecific symptoms of MALS:

- Fatigue after eating

- Nausea/vomiting

- Weight loss

- Constipation/diarrhea

Diagnosis

Patients with MALS often undergo a multidisciplinary evaluation with several specialties including gastroenterology, vascular surgery, general surgery, cardiology, anesthesia pain management, interventional radiology, and psychological assessment. The evaluation includes several gastroenterology tests including upper endoscopy and colonoscopy, motility studies, gastric emptying tests, and serology studies. Not all patients require all the above-mentioned tests, but an expert opinion of a gastroenterologist is critical to guide the diagnostic work-up and to establish that MALS is the most likely cause of the pain. A surgical consultation with an expert on MALS treatment is needed once the diagnosis is contemplated. Among patients who are on narcotic pain medication, anesthesia pain clinic consultation and a therapeutic plan to decrease or discontinue the use of narcotics is important prior to proceeding with invasive treatment.

Figure 2. Computed tomography angiography demonstrates the arterial branches of the abdominal aorta. Note the celiac artery is narrowed on inspiration with significantly worse compression and narrowing on deep expitation.

The compression of the celiac artery is a key component of the diagnosis of MALS. This can be determined using noninvasive vascular imaging such as duplex arterial ultrasound, computed tomography angiography (CTA), or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA). The use of invasive diagnostic angiography is discouraged and is not necessary to diagnose MALS. Regardless of the imaging method, the study should be performed with respiratory maneuvers to demonstrate the active compression of the artery, which is usually worse on deep expiration. Our preference is to start with a duplex arterial ultrasound and then to obtain a CTA with respiratory maneuvers on inspiration and expiration (Figure 2).

A frequent test is the ‘celiac ganglion block’, which involves local injection of anesthetic and/or steroids in the location of the celiac ganglion and adjacent nerves. The test may be used as a surrogate or “therapeutic trial” to anticipate the effects of surgical treatment of MALS, which involves release or removal of the arcuate ligament muscle and fibers as well as removal of the adjacent ganglion tissue (ganglionectomy). The surgical treatment can be done using open surgical or laparoscopic approaches. The rationale for performing celiac ganglion blockage is to try to anticipate if numbing of the sympathetic ganglion or nerves would yield symptomatic relief. It remains controversial if the test is absolutely necessary or not, but we favor obtaining a celiac ganglion block to anticipate if there is a correlation with symptoms. In addition, some patients may benefit from longer lasting effect by local injection of steroids in the celiac ganglion.

Diagnostic tests:

Imaging of the celiac artery compression

- Duplex or doppler mesenteric ultrasound with breathing protocol with inspiration and expiration

- Computed tomography angiography (CTA) with breathing protocol with inspiration and expiration

- Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA)

- Catheter abdominal angiography with contrast dye

Evaluation of other gastrointestinal disorders

- CT scan with and without contrast dye of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis

- Gastric emptying transit motility study with small bowel follow through

- HIDA (hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid) scan of gallbladder

- Endoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy with biopsies

- 24-hour pH impedance probe

- Esophageal manometry

- Gastric tonometry

- Blood work panels

- Chest X-ray

- Electrocardiogram (EKG)

- Stool tests

Treatment Options

The standard treatment of MALS is the release of the celiac artery by open surgical or laparoscopic removal of portions of the median arcuate ligament and ganglionic tissue that surround or completely encase the celiac artery. Regardless of the specific approach, the operation requires meticulous release of the celiac artery by division of muscle fibers from the median arcuate ligament and surgical removal of the overlying lymphatic, ganglionic, and soft tissue. The term “neurolysis” is used to describe the removal of nerve and ganglionic tissue that surrounds the artery in the front, sides, and back. In some patients inflammation and scar tissue is also removed. There are three main types of surgeries to treat MALS, all of which have a role. Surgical treatments can be done using open, laparoscopic, or endovascular methods. Surgical treatment is aimed to reduce or eliminate pain and improve the quality of life for the patient.

Open surgical approach

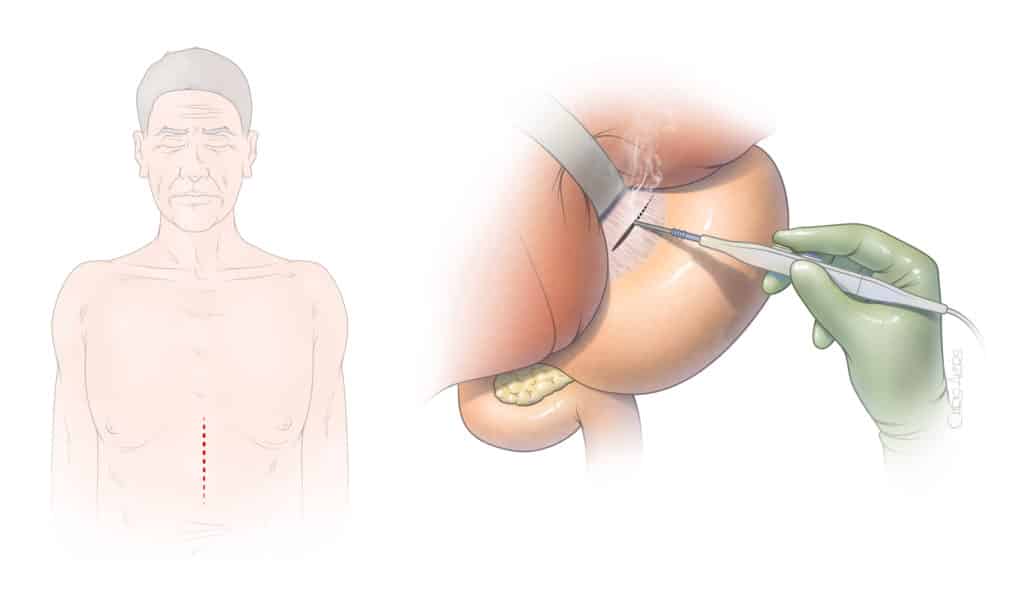

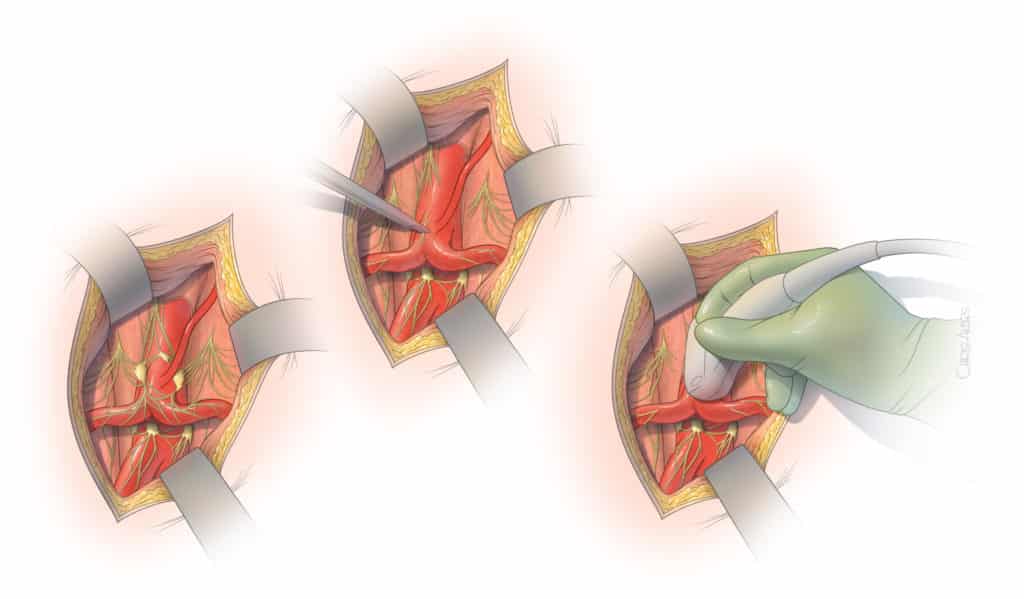

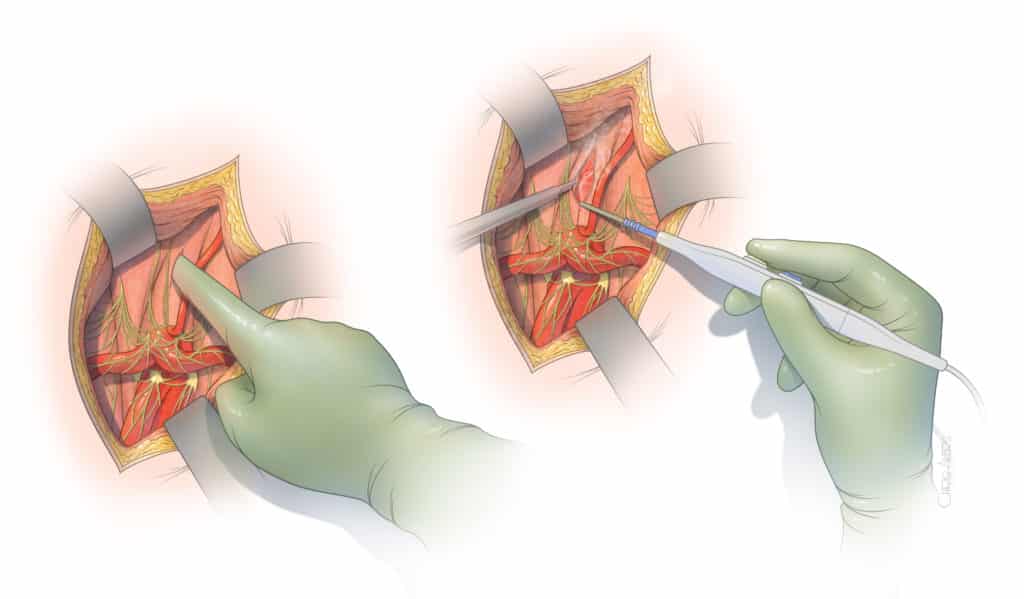

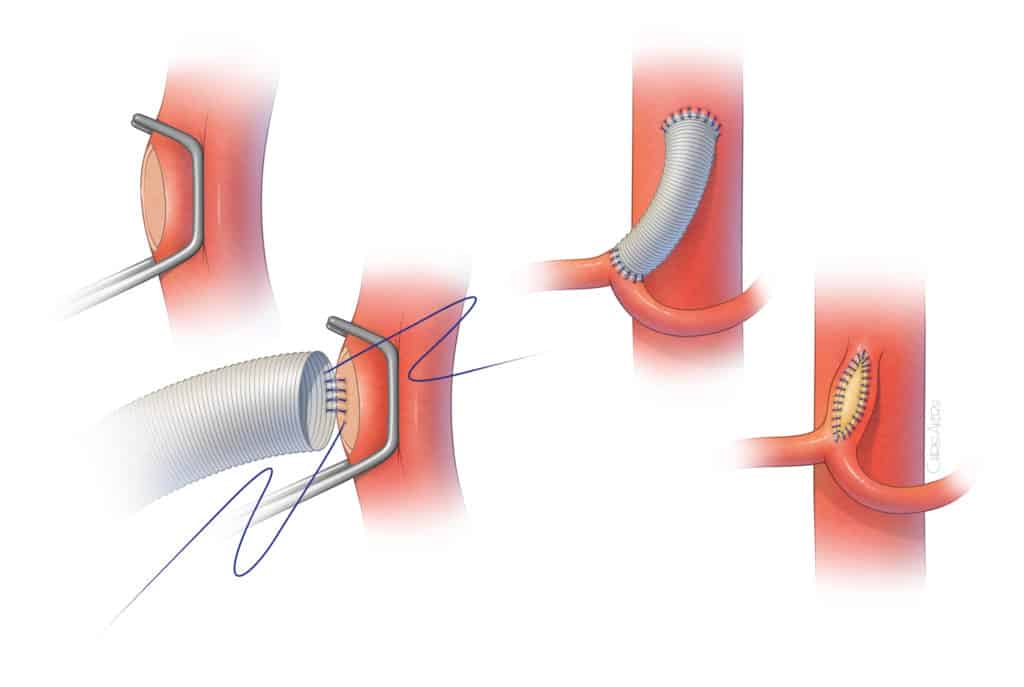

Open surgical release of the median arcuate ligament is most often done using an incision in the epigastric area (Figure 3). The incision typically extends two-thirds of the distance between the lower end of the breast bone toward the umbilical scar. The surgeon exposes the area between the stomach and liver to visualize the median arcuate ligament. Using a combination of sharp dissection with scissors and cautery, the celiac artery is circumferentially freed from the muscle and ganglionic tissue, which are partially removed (Figure 4). Once the artery is freed, our preference is to obtain an intraoperative duplex arterial ultrasound to document that the artery is not severely narrowed or occluded. In cases of severe narrowing, the artery may be immediately repaired by placement of a small prosthetic patch or graft. The main advantages of the open surgical approach rely on the safety of surgical dissection under direct vision and ability to handle any small tear or areas of bleeding. This approach also allows thorough and complete circumferential release of the artery, including the tissue that lies behind the celiac artery (Figure 5). In addition, any severe narrowing can be immediately repaired (Figure 6). The main disadvantage is the need for the incision and larger exposure.

Laparoscopic approach

Laparoscopic release of the celiac artery requires small holes to introduce the camera and surgical instruments without the larger incision. The surgeon works with camera visualization using scissors and cautery. Although the same steps are performed, the operation has the advantage of smaller incisions and the potential disadvantage of risk of bleeding complications or a less thorough release of the ligament. It is critical that the laparoscopic approach is performed by a surgeon with extensive experience in laparoscopy and familiarity with surgical dissection of the celiac artery. Moreover, if laparoscopy is selected, the procedure needs to be performed in surgical environment and by a team that is ready to perform conversion and arterial repair, if needed.

Endovascular approach

Endovascular approach is not recommended as a stand-alone therapy because the muscle and ligament cause persistent compression of the artery, which typically recoils back to its compressed state after the balloon angioplasty. In fact, patients who are treated by angioplasty balloon and stent placement without prior surgical release of the ligament may experience complete occlusion or fracture of the stent due to the median arcuate ligament compression. Most often, endovascular approach is used in conjunction with previous laparoscopic or open surgical release to treat residual narrowing of the artery following the surgical release. In these cases, the procedure can be done under a local anesthetic with a small puncture in the groin artery. A catheter is introduced into the celiac artery and the narrowing is dilated with balloon angioplasty. Typically, a stent is also placed.

Outcomes

Most studies evaluating the outcomes of MALS are retrospective reviews of single center experiences spanning many years and having a relatively small number of patients. For this reason, the level of scientific evidence is low and there is a great deal of discussion among experts with respect to best practices, the role of celiac ganglion block, and superiority of open surgical or laparoscopic approach.

A recent landmark study presented by Gustavo Oderich, MD and colleagues summarized the long-term follow up of 100 consecutive patients treated for MALS. In that study open surgical release was used in 81 patients and laparoscopic release in 19 patients. There were no operative or procedure mortality. One patient treated by laparoscopic release sustained a celiac artery injury extending to the aorta, which required emergent conversion to open surgery. Symptom improvement was noted in 80% of patients, with five-year freedom from recurrence symptoms in 70%. Among patients who answered a questionnaire on average seven years after the operation, 87% reported that they would still undergo operative management if given the choice.

Living with MALS

Living with any chronic illness can be challenging and frustrating for patients and their loved ones. Due to the rarity of the condition, life with MALS can be isolating and scary.

Diet, exercise, mental health, and general self-care is vital to anyone living with MALS.

There are many online resources and national organizations that we collaborate with to coordinate care and resources, and to share experiences.