During the summer of 2020, 17-year-old Fernando Carlos began suffering from shortness of breath.

“It felt like I could only breathe through one nostril,” said Fernando. “I would always have to find a way to get more air in me. Sometimes, I would open the fridge and just breathe in the cold air.”

With COVID-19 surging across Houston, he was screened and tested but the results were negative.

His mother, Karina Enciso, began the search for answers.

“I took him to different doctors. One told me allergies, another told me asthma. He was even given an inhaler,” she said. “But he was not getting better.”

It took months of research, endless phone calls, doctor’s appointments, and even CT scans at an urgent care center before Fernando and his mother were finally referred to Matthew T. Harting, MD, a pediatric surgeon with UT Physicians. Harting diagnosed Fernando with a congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) recurrence.

What is CDH?

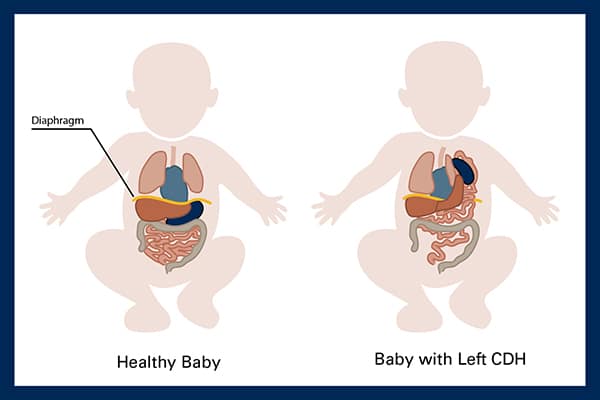

CDH occurs when the muscle that separates the chest from the abdomen, known as the diaphragm, fails to close before birth, leaving a hole. The condition is usually caught by an ultrasound performed during pregnancy.

That hole allows organs that are supposed to be in the abdomen to migrate into the chest, crowding the heart and lungs. Without surgery, the condition can be fatal.

In the U.S., it’s estimated 20-30% of children born with congenital diaphragmatic hernia do not survive.

“It’s a very challenging disease, both for families and clinical teams, partially because it poses a whole host of challenges, requiring a wide range of expertise,” explained Harting, associate professor of pediatric surgery with McGovern Medical School at UTHealth Houston. “These newborns need care in a level 4 NICU. They often need heart and lung bypass support, operations, nuanced critical care, and a whole team of expert physicians to help collaborate. It can be a real challenge early on in life, but if you survive then you can go on and have a very high quality of life.”

Normal childhood after CDH

Fernando is one of those success stories. Born in Guadalajara, Mexico in 2002, doctors gave him a 5% chance of surviving CDH surgery as an infant. He defied the odds, moved to Houston, and went on to play football at Cypress Park High School and nine years of competitive club soccer.

The student-athlete had no idea his childhood condition could return.

Recurring CDH

As with most CDH patients, there is a chance the initial repair to close the diaphragm hole will reopen as their bodies grow and develop.

“There are a lot of reasons why that happens, but it doesn’t mean something was wrong with the initial surgery. It’s a pretty common problem, even in our clinic,” said Harting. “We’re constantly monitoring for recurrence and educating families about the signs of recurrence. We’re actively investigating strategies to minimize recurrence.”

For Fernando, that sign was shortness of breath. Harting says when the hole in his diaphragm reopened, other organs migrated up into his chest, crowding his lungs.

“His entire small intestine and most of his large intestine were located in his chest,” said Harting.

Surgery for recurring CDH

Repairing CDH depends on the size of the hole. Harting says in Fernando’s case the hole was small enough when he was born that the surgeon in Mexico sutured the two sides of his diaphragm together, eliminating the hole. Sometimes, the hole is too large, and a special patch is required.

“That patch is like a GORE-TEX-type material,” said Harting. “It’s a really strong, inert material that can live within the human body for a lifetime.”

Fernando underwent surgery with Harting in June 2021. Initially hoping to use a minimally invasive approach, Harting says there was too much scar tissue, and he had to go in through an open incision to optimally repair his diaphragm.

“In this case, we pulled the muscle together, sutured it, and then we put the patch over the top of it as insurance to avoid another recurrence,” said Harting. “It’s kind of like a belt and suspenders, approach.”

A path forward with CDH

Fernando’s surgery was successful. Now, a junior at Texas A&M University, he is focused on electrical engineering and playing sports again on intramural teams.

“I think Fernando is fine, thanks to him,” said Karina. “He saved my son’s life.”

Speaking through tears, Karina says the very first time she met Dr. Harting, he relieved the heavy burden of fear, stress, and confusion that had built up over months and years. Young adults who survived CDH but then develop a health concern are stuck between pediatric physicians and hospitals who can no longer help and adult physicians and surgeons who don’t see this type of congenital problem.

“He saw Fernando and he said, ‘Yes, I can do it,’ and Fernando’s going to be fine,” she recalled crying. “He was so confident. Even looking at his eyes and his face gave me relief.”

It took months of phone calls, appointments, internet research, scrolling, and emailing, but it all came to an immediate halt Karina says, when they were referred to the new adult Comprehensive Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia (CDH) Program at UT Physicians.

“I felt very welcome,” said Fernando. “The way they were talking and communicating, they made me feel safe and calm.”

Adult CDH program at UT Physicians

CDH impacts about 1 in every 2,500 births in the U.S. and in Houston, it’s estimated that approximately 30-40 babies each year are born with the disease. Specialists are hard to come by and when they do exist, their focus is on pediatrics.

“There are adults all over the world that don’t have a place to turn to because adult providers are less familiar with this disease process and the complications which may result,” Harting explained. “And a pediatrician is not going to follow them as they get older.”

Fernando’s story is too common says Harting, CDH patients aging out of their pediatrician’s office can have a sudden onset of symptoms and suffer through a long search for answers.

“There’s very little research about adult CDH, and we are trying to address that,” he said.

Harting joined the congenital diaphragmatic hernia program at UT Physicians in 2013. Over the last decade, he recognized a need to transition pediatric patients to adolescent and adult care. That focus launched the adult CDH program in 2024, to provide specialized care that cannot be found with a primary care physician.

“We want to build on an already successful CDH program,” said Harting. “This is the right next step.”